Hilandar (fig. 1) is a Serbian imperial lavra in the Holy Mountain. It ranks fourth in the athonite hierarchy. Situated in the North-East part of the Athos Peninsula it is surrounded by hills, and cannot be seen from the coast, although it is only ca. two and a half kilometres far from it. There is a river flowing by the monastery. Hilandar has a familiar appearance of the Mount Athos monastery-fortresses. Nowadays it is in a state of both physical and spiritual renovation (fig. 2) – in 2004 it suffered major damage in a great fire, and in 1990, after a long period of idiorhythmic way of life, the original coenobitic regulations were restored.

History

Founders of Hilandar were St. Simeon, who before his consecration as a monk was the Grand župan Stefan Nemanja, founder of the Serbian late medieval state and of its ruling dynasty, and his son St. Sava, who was to become the first Serbian archbishop. Their original intention was to restore a deserted Greek monastery, that probably went by the name of Helandar and belonged to the estate of the Vatopedi monastery where they at first lived, but it soon grew into a desire to found an independent (from protos and imperial rule) and selfgoverning monastic community.  The general disposition at the Holy Mountain at the time, allowing for an increased presence of foreigners, was in favour of such an idea, as it was the fact that on the Byzantine throne, whose authorization for such an endeavour was needed, sat Alexios III Angelos, father-in-law of Nemanja’s successor the Grand župan Stefan. With the blessing of protos and of the athonite synod, with the Emperor’s authorization and ktitorial support by the Nemanjić family, the monastery began to function within less than a year, in the second half of 1198.

The general disposition at the Holy Mountain at the time, allowing for an increased presence of foreigners, was in favour of such an idea, as it was the fact that on the Byzantine throne, whose authorization for such an endeavour was needed, sat Alexios III Angelos, father-in-law of Nemanja’s successor the Grand župan Stefan. With the blessing of protos and of the athonite synod, with the Emperor’s authorization and ktitorial support by the Nemanjić family, the monastery began to function within less than a year, in the second half of 1198.

Hilandar was clearly meant to be New Zion of the chosen Serbian people, and the practical aspect of its foundation was in St. Sava and St. Simeon’s expression of loyalty of the new Nemanjićs’ state to the Byzantine civilization and acknowledgment of its legitimacy. They made a clear connection between the monastery and their “ancestry”. Simeon did it by passing a vow of ktitorship of the monastery to the future Serbian Kings, and Sava did it by stressing the importance of liturgical praising of ktitors. In the centuries to come, the Serbian state, represented first by Kings and later on also by wealthy feudal lords, supported Hilandar by giving it donations and new estates, by providing funds for new constructions and other requirements, and by protecting the monastery and its estates when they were in danger. Hilandar repaid by maintaining the cults of the state’s and the monastery’s founders, by creating, translating and spreading of Christian literature, by artistic activities and providing the bishops, as well as by diplomatic mediation in delicate situations both in Serbia and between Serbia and the Byzantine Empire.

The fact that the monastery during most of its history did not belong to the Serbian state and the Serbian Church and was from the beginning a constituent part of the Holy Mountain community, taking an active part in its internal and spiritual development (in rejecting the union of Lyon in the thirteenth or supporting hesychasm in the fourteenth century, for example) and jointly benefiting from the Byzantine Emperors’ benevolence, had no bearing on the quality of relations between Hilandar and its home country. Thus it is natural that the Serbian medieval state at its height (from late thirteenth to the second half of the fourteenth centuries) was also reflected in the creative potential of the monastery of Hilandar and in its influence. Construction of a new katholikon (fig. 3), that was in every respect worthy of the most prominent athonite monasteries, during the reign of the King Milutin (constructed in 1293, painted in 1317–1321) should be seen in such a context (fig. 4).

During Serbian dominance of the Athos Peninsula (1345–1371) the position of Hilandar was apparently changed: Serbian rulers practiced imperial policy in the Holy Mountain, presenting gifts to all athonite monasteries and trying to solve conflicts among them, while Serbian monks restored other monasteries and took up residence in them (St. Panteleimon, St. Paul). Nonetheless, Hilandar continued to enjoy undisputed spiritual and intellectual reputation in Serbia, and the Emperor Dušan introduced commassation of its estates, accounting for nearly one fifth of the Holy Mountain territory, and of dozens of other estates (from Chalkidiki and Thessaloniki to the Region of Pomoravlje and Zeta), among which the basic inherited estates were those in Kosovo and Metohija. Later on, in the first part of the fifteenth century, when Serbia regained the status of a powerful and prosperous state, the reigning dynasties of Lazarevićs and Brankovićs looked upon Hilandar as a link to the holy dynasty of Nemanjićs, but their support to the monastery could not measure up to that of the Nemanjićs neither in size nor in reliability, since the Serbian territories, including the Hilandar estates, were gradually coming under Turkish power.

Having come under the rule of new, non-Christian masters, the athonite monastic community had to protect itself against violence, to struggle to preserve its autonomy, and to secure funds for payment of new taxes. Although deeply affected by deprivation of major part of their income, the monks of Hilandar were fully committed to the struggle for the common causes, displaying an exceptional ingenuity. They managed to find fairly reliable supporters among reigning dynasties of other orthodox states (Wallachia, Moldova, and Russia), which thus built up their own reputations, and sometimes also among wealthy individuals, to protect their own interests by gaining a better insight in functioning of the Turkish state, and to use every opportunity to extend their own estates, or to regain them if they had previously been forced to sell them. Thanks to a capable monastery administration, the brethren survived and even increased in number, and during the period of ca. two centuries (up to the second half of the seventeenth century) the monastery of Hilandar ranked third in the Holy Mountain hierarchy.

At that time, the monastery was still predominantly populated by Serbian monks. It continued to maintain regular contacts with Serbs everywhere, especially those living in the Habsburg Monarchy, and had an important role in building their historical conscience and ascertaining their identity and historic continuity. At the same time, in the eighteenth century, the Bulgarian monks in the monastery grew in number, thanks mainly to financial support of Bulgarian merchants, and the process culminated in the life and deeds of the archimandrite Pajsije of Hilandar. The evident benefits the Serb-Bulgarian symbiosis meant for Hilandar were partly diminished by quarrels that resulted from the creation of national states process in the nineteenth century. At the turn of the nineteenth and twentienth centuries the monastery once more became sanctuary primarily of “those people of Serbian origin who opted for monastic way of life”, as stated in the Emperor Alexios III’s founding charter.

Cults and Inheritance

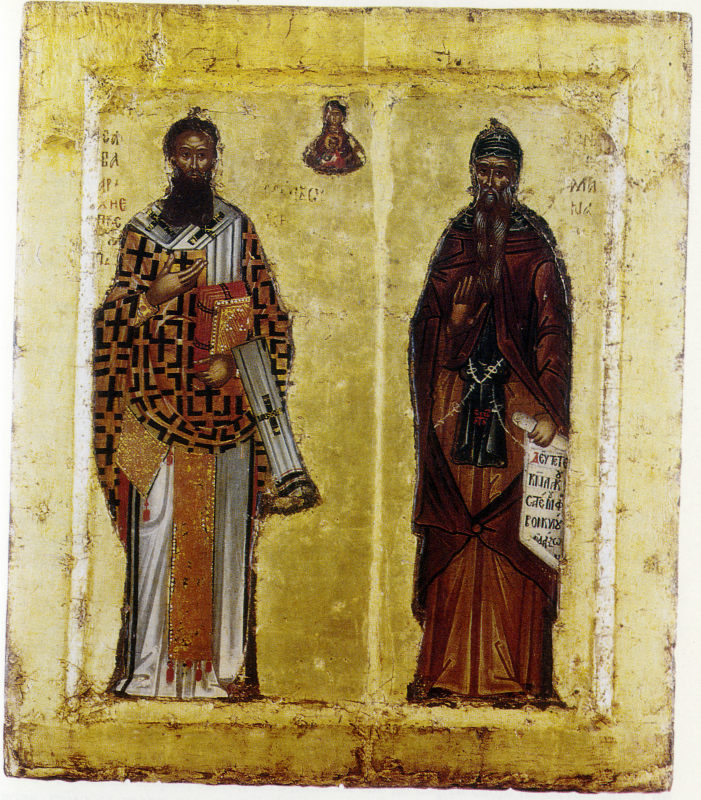

During the eight centuries of the monastery’s existence numerous holy objects were compiled, including a fragment of the Holy Cross, miraculous icons and a number of sacred relics. The most respected cult, however, remained the cult of the monastery’s holy founders Simeon and Sava (fig. 5). The days of their passing away are two of the four monastery celebrations, and on the second day of the main celebration, Introduction of the Holy Theotokos, a joint akolouthy is served. Their contemporaries and fellow residents from Hilandar, deeply impressed by their deeds, recognized them as saints and first left short notes about them, but later on two brilliant hagiographies were written by Domentijan. Both Domentijan and, later on, Teodosije, who supplemented and completed the glorifying texts about them, identify St. Simeon’s shrine (his relics were transferred to the monastery of Studenica already in 1206/1207) as the Founders’ main „place of memory“ within the monastery ground. Its significance was confirmed during restoration of the church, by lifting the shrine above the ground level and also by its new iconography (fig. 6).  Teodosije is also responsible for creation of a joint cult of the “sacred two” as praying intercessors for Serbian Kings, state and people before God. The monks of Hilandar have for centuries spread these cults outside their monastery by taking with them on their travels small parts of the saints’ relics, their hagiographies and icons. The vitality of the Holy Founders’ cults is symbolized by the familiar sight of Hilandar – grapevine that grows from Simeon’s shrine and still brings fruit (fig. 7).

Teodosije is also responsible for creation of a joint cult of the “sacred two” as praying intercessors for Serbian Kings, state and people before God. The monks of Hilandar have for centuries spread these cults outside their monastery by taking with them on their travels small parts of the saints’ relics, their hagiographies and icons. The vitality of the Holy Founders’ cults is symbolized by the familiar sight of Hilandar – grapevine that grows from Simeon’s shrine and still brings fruit (fig. 7).

The Hilandar inheritance in its entirety is usually considered to be among the most valuable in the Holy Mountain, together with the inheritances of the monasteries Vatopedi and Lavra of St. Athanasios. The importance that was attributed to the monastery from the very beginning resulted in endeavours that everything that is created in it or for it should be of a representative character. As far as iconography is concerned, of special importance are the frescos from the beginning of the thirteenth century on the external walls of the Chapel of St. George, which is a unique and formerly sepulchral architectural complex belonging to the tower dedicated to the same Saint, with series of scenes depicting St. George’s life and from The Canon on the Egress of the Soul.  Remnants of half a century younger frescoes of the altar in the Chapel of Transfiguration Pirgos (fig. 8)have to be mentioned too, as well as the exquisite frescoes of the main church, originating from second decade of the XIV c.

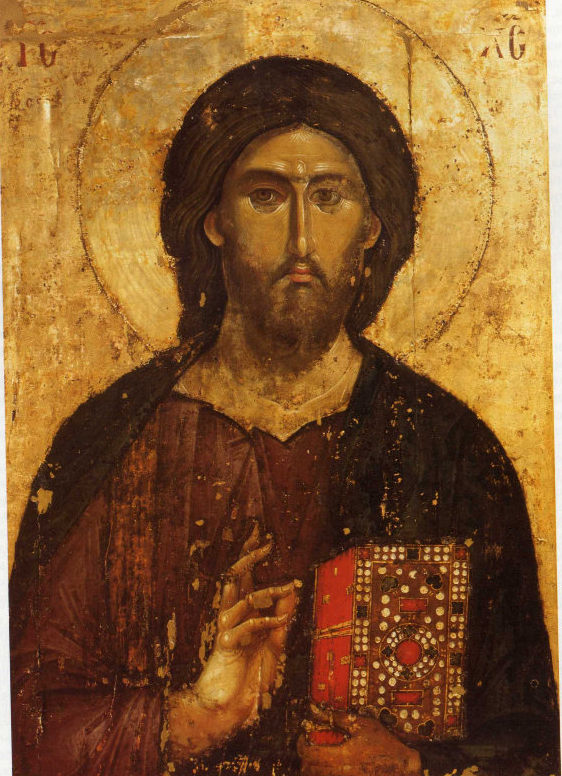

Remnants of half a century younger frescoes of the altar in the Chapel of Transfiguration Pirgos (fig. 8)have to be mentioned too, as well as the exquisite frescoes of the main church, originating from second decade of the XIV c.  Among icons, in addition to the Holy Theotokos Tricheroussa (Bogorodica Trojeručica, (fig. 9)), that scientific research places in the fourteenth century and tradition claims to be of Jerusalem origin, and which has the stature of hegoumenia of the monastery, the mosaic icon of the Theotokos Hodegetria (fig. 10)from the second half of the twelfth century, the patronal icon from the period when the monastery was founded, the icons (probably thronal) of Christ (fig. 11) and Theotokos from the third quarter of the thirteenth century, and a number of icons from the Deisis presentation on the iconostasis originating from mid fourteenth century, should be singled out, as well as the icon of Introduction painted in the Crete school style, and the Russian icon of the Unhandmaded image of Christ from the sixteenth century.

Among icons, in addition to the Holy Theotokos Tricheroussa (Bogorodica Trojeručica, (fig. 9)), that scientific research places in the fourteenth century and tradition claims to be of Jerusalem origin, and which has the stature of hegoumenia of the monastery, the mosaic icon of the Theotokos Hodegetria (fig. 10)from the second half of the twelfth century, the patronal icon from the period when the monastery was founded, the icons (probably thronal) of Christ (fig. 11) and Theotokos from the third quarter of the thirteenth century, and a number of icons from the Deisis presentation on the iconostasis originating from mid fourteenth century, should be singled out, as well as the icon of Introduction painted in the Crete school style, and the Russian icon of the Unhandmaded image of Christ from the sixteenth century.

A very rich collection of graphics, a collection of applied arts objects (including the Venetian diptych and also inscription of Despotess Jelena, the future nun Jefimija, on another diptych, with a short, but deeply moving and original prayer expressing pain caused by death of her child), the archives containing invaluable documents by Serbian, Greek, Russian, Vlach, Moldovian, Bulgarian and Turkish auctors from the twelfth to the seventeenth centuries, several thousands of seventeenth to nineteenth c. books, all make part of the monastery’s Treasury (fig. 12).

A very rich collection of graphics, a collection of applied arts objects (including the Venetian diptych and also inscription of Despotess Jelena, the future nun Jefimija, on another diptych, with a short, but deeply moving and original prayer expressing pain caused by death of her child), the archives containing invaluable documents by Serbian, Greek, Russian, Vlach, Moldovian, Bulgarian and Turkish auctors from the twelfth to the seventeenth centuries, several thousands of seventeenth to nineteenth c. books, all make part of the monastery’s Treasury (fig. 12).

Manuscript Collection

The collection of manuscript and early printed volumes was formed in the nineteenth and in the beginning of the twentieth centuries by merging the codices from the monastery and from its kellias into a joint fund. Structure of the collection was defined by the meritorious monk Sava, Czech by birth, when the library was reorganized at the turn of the centuries. More than a thousand manuscripts with Slav codices or their fragments (from the end of the twelfth until the beginning of the twentieth centuries), eighty one early printed books and ca. hundred and eighty Greek manuscripts are kept in the Hilandar library today, making it by far the richest Serb library of the kind. Its size can be partly attributed to the fact that Hilandar shared the Holy Mountain autonomy, and had a much more peaceful history than the monasteries in Serbia, in spite of frequent attacks by military troops or robbers, or of misfortunes such as the great fires in 1722 and 1776 in which both books and documents were destroyed.

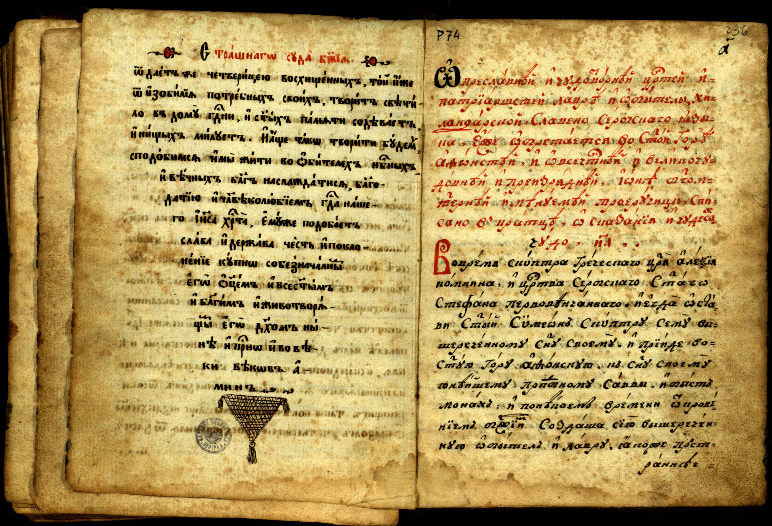

More than four fifths of items making the present collection of Slav manuscripts were made in Hilandar or in its sketes, where hesychastic way of life was subordinated to asceticism and, at the same time, allowed for undisturbed intellectual activities. This primarily refers to the hermitage of St. Sava of Jerusalem in Karyes and to the Skete of Transfiguration, later of the Holy Trinity, in Saviour’s Water site, where books have been written and collected since the thirteenth century. As for the manuscripts of external origin, some of them were ordered by the monastery itself or to be given as a gift to it. It is an interesting fact that only ca. twenty codices previously belonged to some other athonite monastery. On the other hand, speaking of dissipation of the fund, beside books lost through the natural decaying process or in the already mentioned fires, a large number of books became part of other collections throughout the world, from Sinai and Vladivostok to Oxford and Paris. Starting from the sixteenth century, the monks of Hilandar themselves gave valuable books as gifts to their protectors or organized their copying for monasteries and churches in their homeland. But most of the estranged books changed place in the nineteenth century as a result of a sudden increase in scientific interest for the monastery. The most valuable document (Simeon’s Founding Charter, now lost) and the book (Miroslav’s Gospel) were presented by Hilandar monks to King Aleksandar Obrenović, in other words to Serbia, on the occasion of his visit to the monastery in 1896. Finally, at least several codices of Hilandar origin were part of the National Library of Serbia collection, which included over one thousand manuscript volumes and was destroyed during German bombing of Belgrade in April, 1941. Only one manuscript – Serbian hagiographic miscellany ((fig. 13))by the scribe Taha Marko (NLS 17) – was saved, thanks to the fact that it was at the time of bombing in the hands of historian Vladimir Ćorović for the purpose of research.

Profile of the collection corresponds to its purpose: most of the manuscripts belong to liturgical books, that are used in everyday communal worship, and to various theological and monastic-ascetic literature, depicting both theoretical and practical aspects of Christian life. There are also texts that are not strictly theological, but of an instructive character: for example, the oldest Slav translation of Stefanit and Ichnilat (Moscow, Russian State Library, Grigorovič F 87 n 54 М 1736) was part of the monastery collection, and today the collection includes copies of Barlaam and Joasaf (Hil. 422), from the fourteenth century, and ofAlexandrida (Hil. 296), from the eighteenth century, one copy of each. The purpose of some apocrypha was to fulfill the wishes in the domain of fantasy, while translations of Byzantine chroniclers’ works were meant to satisfy interests for the world’s history, because copies or reliable editions of the relevant books of the Old Testament were not available. In the domain of law, the collection includes copies of Dušan’s Code (Hil. 300) from the fifteenth century, and the Agriculture Law (Hil. 466) from the same period, as well as major medical texts – an anthology that includes Hiyatrosophy (Hil. 462) from the fourteenth century, and the famous Medical Codex of Hilandar (Hil. 517) from the sixteenth century.

In the remain of this paper, the attention will be payed to some of the relevant books that came to existence in the monastery, notwithstanding their present location, or were in an extended period used in its activities and thus have become an intrinsic part of its being, irrespective of their provenance, presented in chronological suite and also in their own context.

The Books of Hilandar and their scribes.

St. Sava was compelled to search for the books that were needed for revival of monastic life in the immediate vicinity, i.e. among Greek and Slav, mainly Russian and Bulgarian codices on Mount Athos. Some of the books were, certainly, procured from Serbia, which is witnessed by the still barely visible structure of the original library of the monastery: in addition to the founding documents it included liturgical codices, of which only Russian chanting manuscripts with neumatic notation, Sticherar (Hil. 307) from the late of the twelfth century, and Heirmologion(Hil. 308) from the same time or the early thirteenth century are today present in Hilandar, while so-called Hilandar Folia (Odessa, State Scientific Library R 1/533), a Glagolitic passage from Teachings of St. Cyril of Jerusalem from the tenth or eleventh century, and Bulgarian Parimeinik (Moscow, RSL, Grigorovich F 87 n 2 М 1685) from the twelfth century, are in Russia. Today two richly embellished Aprakoses, Miroslav’s Gospel (Belgrade, National museum, fig. 14) and Vukan’s Gospel (Saint Petersburg, Russian National Library F n I 82), originating from the last decades and the very end of the twelfth century respectively, for which it can only be assumed that they were in the monastery from its foundation, are also out of the monastery. The significance of these books is well-known, so that the attention will be payed to the founding documents, more precisely to charters and typicons, although they belong to the documentary domain, in order to enable at least partial understanding of the monastery’s position and its structure, which were prerequisites for its bookmaking activities.

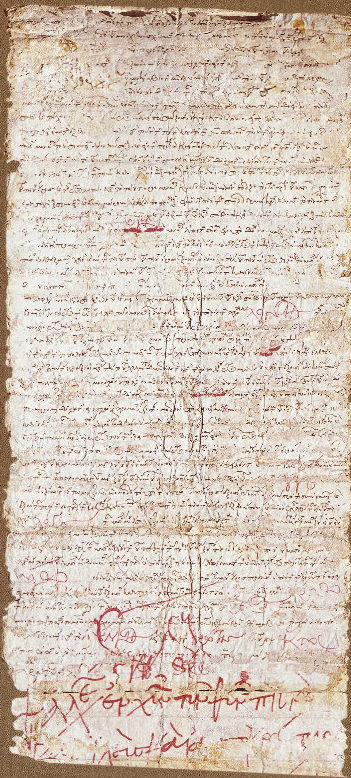

– Chrysobull scrolls of the Emperor Alexios III Angelos (fig. 15), dating from June 1198 and June 1199, were issued on the occasion of Sava’s visits to Constantinople and establish Hilandar as the imperial lavra, not subjected to the power of protos, similar to the status of other foreign athonite monastic communities (the Iviron monastery and the monastery of Amilfitans). Moreover, the Emperor did not personally confirmed the appointment of a new hegoumen, as it was the case with other imperial monasteries, but he sent his scepter to Hilandar as the symbol of his presence at the electoral ceremony, which was an unprecedented privilege, yet not the only one. The Emperor Alexios gave Simeon and Sava full power over the monastery and explicitly set it aside for the use by monks of Serbian origin.

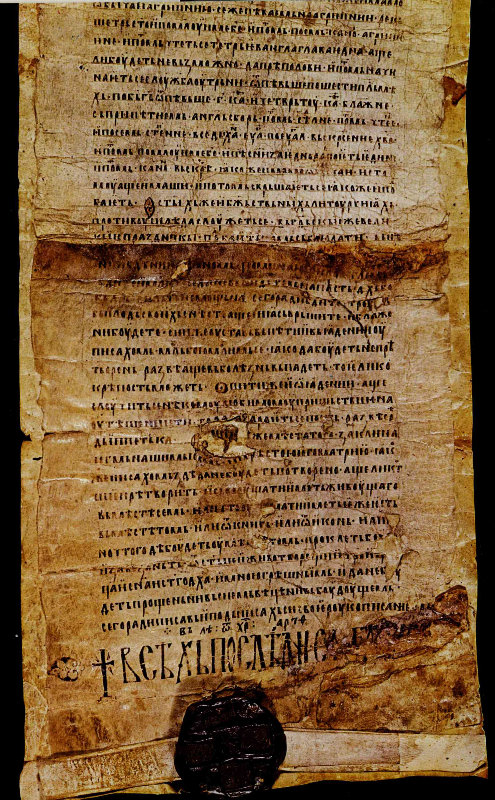

– The Founding Charter of Stefan Nemanja from the second half of 1198. There is no doubt that St. Sava took part in making of the document that contains the nucleus of his literary work and, by that, of the original Serbian hagiographic literature. Nicely stylized arenga defines the position of the young Serbian state in the world and explains Nemanja’s motives to abdicate, to take vows as a monk, leave for the Holy Mountain and build Hilandar, and vows his successors to ktitorship. The charter presents the monastery with the basic inheritable estate near Prizren as a gift. By a charter that was issued between 1199 and 1202 (Hil. Arch. 1) the Grand župan Stefan Nemanjić soon added a number of villages in the vicinity of Peć to the estate. Thus Simeon gave his successors an example of the scope and purpose of their power, shaping their reigning ideal by his own deeds as the King, the monk, and the Saint.

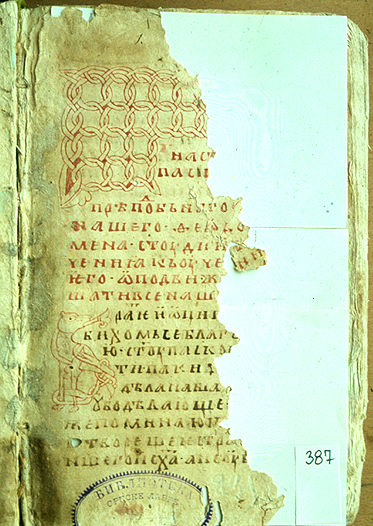

– The Typicon of Karyes (Hil. Arch. 132/134, fig. 16) from 1199 has been preserved on a scroll, perhaps as a copy dating from the beginning of the thirteenth century. It was written by St. Sava for the hermitage intended for a more severe, ascetic life of two or three monks. The hermitage was founded in Karyes, the seat of the athonite administration, it was dedicated to St. Sava of Jerusalem. St. Sava was named after this Saint, took his life as an example, and used his typicon as a model for his own ascetic codex. By reconciling the kelliotic and coenobitic ways of life he enabled a full spiritual development of every single monk, corresponding to his abilities.

– The Typicon of Hilandar (Hil. Arch. 156/158) from 1199 or 1200 has been preserved as a copy made directly from the original in the early thirteenth century. His author is also St. Sava and it was made following the model of the Typicon of the monastery of the Theotokos Evergetis in Constantinople, or, more precisely, it was adjusted to the life of Serbian monks in the Holy Mountain and the detailed instructions for liturgical cycles of immovable and movable feasts were omitted. According to the typicon everything is subbordinated to the community: the pillars of monastic life are obedience to the hegoumen, attendance of communal worship and meals, and regular confessions and communions. Obstinacy is prevented, the process of election of monastery administration is regulated and hierarchy is defined. Regular keeping of income and expense books was obligatory. Celebration of major holidays and memorial services to ktitors, as well as reading of Typicon during the meal were also regulated. Using the Hilandar Typicon as a model, Sava wrote another one, Typicon of Studenica, that was to become a standard for later Serbian monastery statutes.

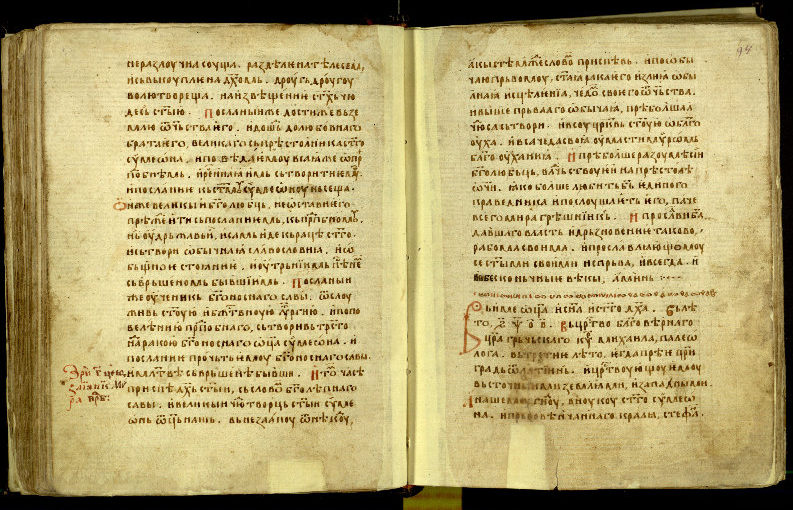

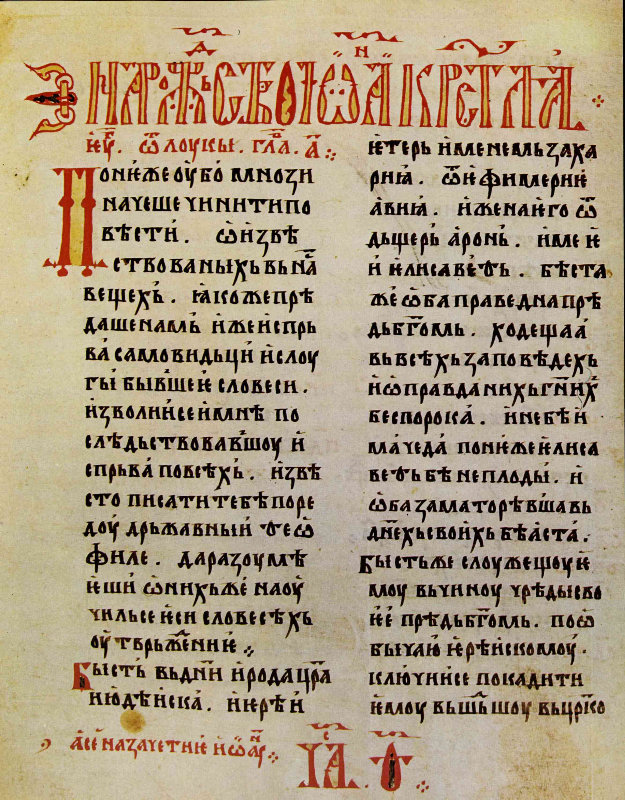

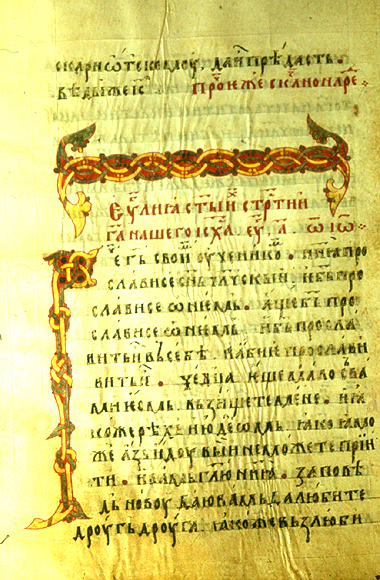

Intensive literary and copying activities soon emerged in Hilandar and in many ways shaped Serbian medieval literacy. The influence of the cult of holy founders to original creative activities in the thirteenth century has already been mentioned. Making of a few dozens of copies of known works in that century can be documented. They could be classified by their ornaments which bear resemblance to the two cited richly embellished codices from the previous century. For example, the oldest Serb-Slav Tetraevangelion(Hil. 22), with concordances written on page margins, and Aprakos (Vatican, Bibliotheca Apostolica, Cod. Vat. Slav. 4), with a note by Desoje, probably a scribe of the later Bosnian governor Matej Ninoslav, can be brought into connection with the Miroslav’s Gospel. Parimeinik (Hil. 313) and the oldest Serb edited anthology of dogmatic and moral instructions, Teachings of Theodor Studites (Hil. 387, fig. 17), both from the first half of the century, have a number of resemblances with the Vukan’s Gospel.

Only two scribes are known to us by name. One of them copied Teodul’s Octoechos (Hil. 158) in Hilandar, to be used in the kellia of Karyes. A note left by the other one, Teodor Gramatik, who copied the Hexameron of Hilandar (Moscow, State Historical Museum, Synod. 345), the oldest known Serbian anthology of interpretations of the Scripture, bear witness to the fact that copying of books was a necessity, but it also meant a number of challenges. Teodor writes about a severe exile of the beardless, being one of them himself, from the Holy Mountain. His spiritual father, none less than the famous Domentijan tried to protect him, but only with a limited success. Thus Teodor had to finish his copying of the book, which he began in the Transfiguration Pirgos, on another Hilandar estate outside the Holy Mountain.

At the turn of the thirteenth and the fourteenth centuries, Life of St. Pankratios Tavromenes (Saint Petersburg, RNL, Q n I 33) was copied from the Russian original from the skete monastery of Ksilurg, and from the same period date cited Stefanit and Ichnilat and the Paris manuscript of Life of St. Simeon by Stefan Prvovenčani (Paris, National Library, Cod. Slav. 10), which has until recently been considered to be its best preserved copy. It was only the announcement of the “golden” fourteenth century, the most brilliant period of literary activities in Hilandar.

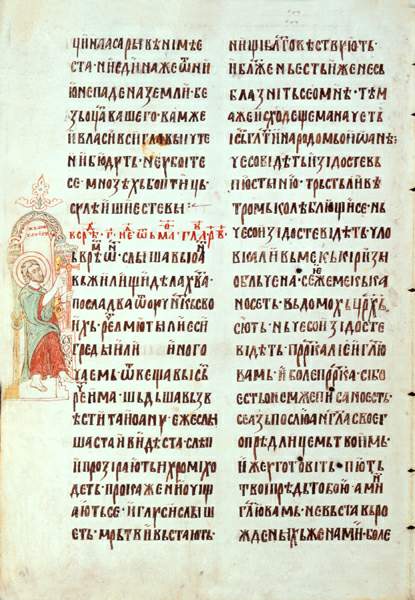

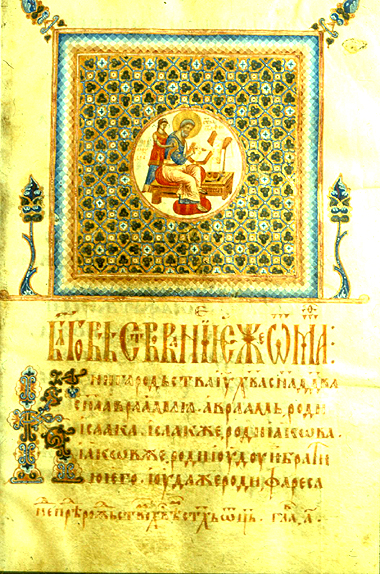

The King Milutin’s Tetraevangelion (Hil. 1, fig. 18) from 1316, copied at the order of the King bydijak Georgije (Radoslav), the scribe of St. Stefan’s Chrysobull, was intended for the hermitage of Karyes. Scribe’s brilliant note, similar in style to the introductions of the Serbian charters, speaks of the world order and draws a parallel between the dynasty of Jesse and the holy dynasty of Nemanjićs. At the same time, at the kellia of Karyes hegoumen Nikodim, later Serbian archbishop, began to translate theTypicon of Jerusalem, new basic canonic statute of the Serbian church. The codex of Nikodim’s Typicon from 1319 was destroyed in the ruins of the National Library of Serbia. These codifying activities contributed to the creation of the most important works and copying achievements of that period. The connection between them and the literary work of the monk Teodosije (although he precedes it), who, in addition to writing original church poetry and prose, adapted some old works as well, has not yet been fully explained. Teodosije’s writings are included in twenty three different codices of the Hillandar collection. The importance of introduction of the new typicon is best reflected in the books of Roman, an exquisite scribe from the first half of the century. Roman’s Typicon (Berlin, State Library, Wuk 49) from 1331 was enriched by a specific scholia, i.e. by notes on the page margins pointing to variants from other translations or from the Greek original. The same codex was supplemented by notes on the Serbian Kings’ deaths. Aprakos (Hil. 9, fig. 19) by the same scribe, of a complete aprakos kind, include a number of liturgical comments. The book originates from 1337, and already its original was nicely embellished, and in 1360 it was further enriched with exquisite miniatures of evangelists, made by a Greek painter, who was also the author of Deisis presentation for the iconostasis of the cathedral.

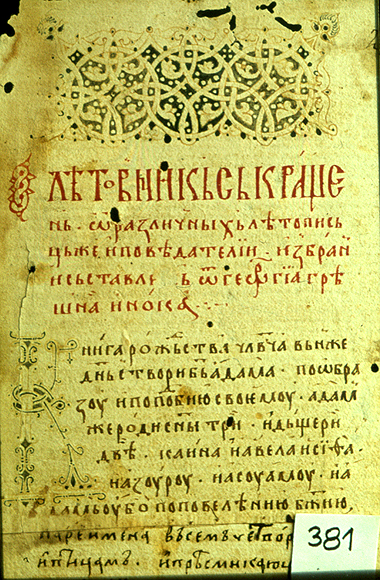

Translation activities were intensified over the centurie, which is primarily explained by a need to understand and to take part in the hesychastic developments. In addition to copying the works of the ancient hesychasts (i.e. of St. Ephraim the Syrian and St. Isaak the Syrian), the works of contemporary authors, such as patriarch Kallistos, Gregorios Sinaites and Philotheos Kokkinos, were also translated and edited. Amongst the texts of the two latter authors, in a Canon (Hil. 342) that originated between 1364 and 1374, there is the only copy of the monk Jefrem’s work, one of rare original literary works created in Hilandar in the second half of the fourteenth century. The greatest achievement of this kind is the Dečani anthology Homilies of Saint Gregory Palamas(Dečani 88) which includes translations of some texts belonging to the famous polemics between Palamas and Barlaam of Calabria, whose originals are missing. Beside the hesychasts’ works, in mid of the century, most probably during the Emperor Dušan’s reign, The Chronicle of George Amartoles (Hil. 381, fig. 20) was subject of linguistic adaptation, obviously in the context of perceiving the position of the newly created Serbian Empire in the world. At that time the scribe of Stefan Dušan’s Tetraevangelion(Hil. 15), the Great Lavra monk who uses a Greek original from his monastery seriously warns the future copyists not to change his text: „because our people have diminished many books, not knowing the mightiness of greek language“.

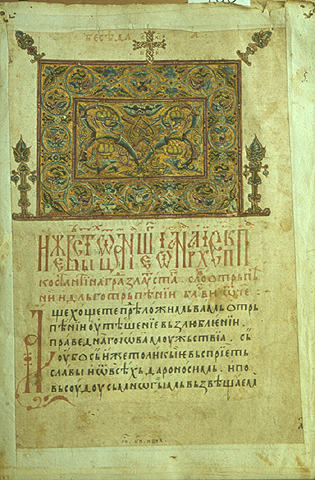

In mid and in the third quarter of the fourteenth century the bookmaking skill reached such heights as to be able to set calligraphic and ornamental standards. Names of a number of scribes are known to us. By scope and quality of their work and specific characteristics of their writing, some of them actually formed small copying “schools”, among them being Simeon, the monk Jov (scribe of the cited Chronicle of George Amartoles), anagnost Jovan, Damjan–Josif, Taha Marko, and, probably, Danilac Jednooki. In that period ornaments of so-called “Balkan style” were still used (like in Pentecostarion of the Wretched Janko (Hil. 265), whose scribe, after having completed his job, wrote: “Take a rest, wretched Janko, you worked too hard”), and flags and initials of the refined “neo-Byzantine style” were at their height and in some cases they could match the best of their Greek models (Aprakos of Nikola Stanjević (Hil. 14) that was written by the monk Teoktist, or the famous Tetraevangelion of Patriarch Sava (Hil. 13, fig. 21), for example). It is not surprising that the Hilandar books of that period were highly respected and were in considerable number present in the collections of other Serbian monasteries, most of all of the monastery of Dečani and in the Patriarchate of Peć.

In the first half of the fifteenth century support of the dynasties of Lazarevićs and Brankovićs to the Holy Mountain alleviated to some extent the immediate effects of Turkish conquests. It was the period of emergence of original literary works in Serbia, and for Hilandar it meant the prominent scribes’ visits to the homeland as well as new translations or translation editions of Byzantine works, which is witnessed by a number of detailed notes. That testifies to the fact that in Serbia Hilandar continued to personify spiritual supremacy, and the titles that were in demand reflect an increase in interest for theological perception of the world history (of its spiritual aspect), coloured by apocalyptic tones, due to bitter experiences caused by the Turkish conquests (some Old Testament books, Chronicle of John Zonaras, Haexameron etc).

The learned monk Grigorije, for example, listed the antique and medieval literature on the earliest period or human history known to him, and mentioned that he got the extract from Paralipomenon by John Zonaras, that he copied in 1408 (Moscow, RSL, Volokalmskoe sobr. 655), directly from despot Stefan. The similar situation was with the monk Gavrilo who used a Greek excerpt from the monastery Esphigmenou to translate and copy Commentary on the Book of Job by Olimpiodoros of Alexandria (Moscow, Synodal Library 63(202)). Perhaps the most famous was the note made by the scribe ofRadoslav’s Gospel (fig. 22) from 1428/1429, a Monk from Dalša: in an almost melancholic manner this Hilandar monk told the story of his visit to the homeland, at despot Stefan’s invitation, and of the books he was to copy for him, but also of the circumstances in Serbia after the despot’s death. The Hilandar collection today includes also a number of books that were written in Serbia by the best scribes of the mid fifteenth century, like David and Stefan Domestik. The latter one wrote a manuscript copy of Metaphrastes (Hil. 400, fig. 23), for example.

A very important convoluted Miscellany (Hil. 463) originates from the second half of the fifteenth century. It includes the only known copy of a work by Genadije Svetogorac, “hieromonk and domestic” as he called himself, dedicated to St. Peter Hagioretes, as well as the original Life of the Elder Isaiah (written by one of his disciples), who was a Serb born in Kosovo, hegoumen of the restored monastery of St Panteleimon, translator of Pseudo-Dionysios the Aeropagite’s works, and mediator in reconciliation of the ecumenical patriarchate and the Serbian Church. Well-known and at the time increasingly often copied texts by the monk Černorizets Chrabar and Constantine the Philosopher on language, alphabet and orthography are also included in this book. Traces of the Glagolitic alphabet can be discerned in the Miscellany, as an interesting repetition of its use.

The sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries were the period when the Monastery of Hilandar got accustomed to the Turkish power, and it had a favourable effect on its bookmaking activities. Also, more books kept coming to Hilandar from the outside world, especially those that were written to be presented to the monastery as a gift (Danilo’s Collection from 1553 (Belgrade, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts 14509), copied in the monastery of Mileševa). A common practice in that period was carrying books on travels whose purpose was search for donations. On one of such travels, the monk Grigorije from the hermitage of Karyes came across a Russian copy of the Jewish War by Titus Flavius Josephus, and translated it without having had a possibility to edit the text, since it was impossible to find a different copy of the book (Hil. 280).

Today we know of a number of prolific scribes from the seventeenth century. Averkije, who lived in the first half of the century, should be singled out for his copying activities, but also for his editorial and literary work. For each of monthly issues ofPanegyrics (for example, Hil. 444), that he copied in Karyes, he used seven or eight excerpts, and sometimes he wrote interesting comments on the text, such as: “Do not lie, you heretic, Makarios have found it and not you!“ Damaskin, who traveled to Russia in search for donations and became very familiar with Russian literature, also copied books. Greek athonite monks degraded him for practicing some of the Russian church customs (making the sign of the cross with two fingers) and transferred him to a Turkish jail. A Russian, Samuilo (Bakačič), came to the Holy Mountain in the second half of the century and in Hilandar, at the location of Spasova Voda, in St. Ana’s skete, and elsewhere he translated a number or monastic-ascetic works of Russian and Byzantine literatures.

In the sixteenth century books were mainly embellished by the scribes themselves and were not of a great artistic value. Better embellished books were also dominated by the Holy Mountain conservatism of the time. In the following century a certain return to the models from the fifteenth century was witnessed, and the scribe Orest, for example, wrote a very nice Klimax (Belgrade, Museum of Serbian Orthodox church, Grujić 187). The merit of hiring a brilliant Greek iconographer, who painted flag medallions at the beginning of text passages in the Aprakos from 1660 (Hil. 107, fig. 24) in the style of Crete painting, goes to the capable prohegoumen Viktor, who himself copied books. The book is also valuable for its contents because it is a rare example of a complete prominent Apostle, both in respect of calligraphy and a proper Resava monastery orthography.

Handcopying of books persisted in both nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Collection of material and writing of the Slav-Bulgarian History, a fundamental work or Bulgarian historiography, whose author was prohegoumen Pajsije Hilandarac (1762), was a most worthy literary endeavour. Among its scribes were Kiril (Živković), later to become the bishop of Pakrac, who copied Teodosije’s Canons to St. Simeon and St. Sava in eight modes (Hil. 624), and Teodosije, the most prominent Hilandar copyist in the second part of the century. He was Serb from Croatia, who not only copied books but “translated” them into the “Church-Slavonic” language as well (Hil. 799, for example). Not to forget he monk Kiprijan who in 1774 translated Sticherarion(Hil. 581) from Greek and left a note about it and his own seal in the book.

The last original Hilandar literary work, that can be considered as a part of the postmedieval literary corpus, came to existence at the beginning of nineteeth century. It was The Miracle of the Holy Theotokos Tricheroussa of Hilandar, included in theMiscellany (fig. 25) from 1804 (Belgrade, NLS 74). Today, personal books and notebooks from that period can be also found it the monastery’s library, as anachronic reflections of an obsolete way of spreading written words.

The vine of Saint Simeon helps infertile women

One of great miracles is the Vine of St. Simeon which sprouted out by itself from his grave after St. Sava dug out his bones in 1206 and transferred them to Serbia in order to make peace between his brothers Vukan and Stefan. The vine has been bearing fruit for almost eight centuries without special care and protection, except pruning.”

“A vine sprouted from St. Simeon’s (Stefan Nemanja’s) tomb. It still yields fruit after 800 years. Barren women become mothers after they have tasted the grapes from the vine. This miraculous vine has brought luck to many childless married couples who now have their posterity. One can become acquainted with the contents of a great number of letters sent to the monastery by the thankful parents who consumed grapes from Nemanja’s vine.

(http://slovo-aso.cl.bas.bg)