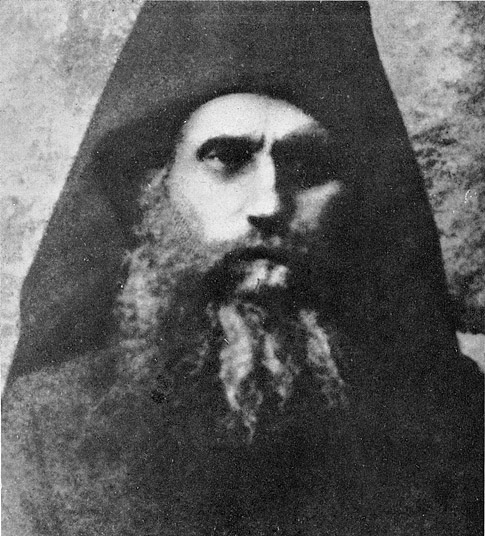

Schema-monk Siluan of Mt. Athos (his secular name was Semyon Ivanovich Antonov) was born in 1866 in the village of Shov, Lebedinsk region of the Tambov district of Russia. He first arrived on Mt. Athos in 1892, was tonsured in 1896 and took the vows of the schema in 1911. His period of obedience was served at the Mill, the Kalamarey Metoch (monastery territory outside Mt. Athos), the Old Nagorny Rusik and the Oeconomia. He died on the 24 (11) September 1938. These brief facts are taken from the Athos records.

Schema-monk Siluan of Mt. Athos (his secular name was Semyon Ivanovich Antonov) was born in 1866 in the village of Shov, Lebedinsk region of the Tambov district of Russia. He first arrived on Mt. Athos in 1892, was tonsured in 1896 and took the vows of the schema in 1911. His period of obedience was served at the Mill, the Kalamarey Metoch (monastery territory outside Mt. Athos), the Old Nagorny Rusik and the Oeconomia. He died on the 24 (11) September 1938. These brief facts are taken from the Athos records.

Between “born” and “died” there seems very little to say; but to speak of someone’s inner life before God is a forthright, audacious act. To open up the “innermost heart” of a Christian on the world stage is almost sacrilege. But in the knowledge that for the Elder, who left this world a victor over it, there is nothing to fear; nothing will disturb his eternal rest in God, so we — who also search for righteousness — can attempt to discover his morally rich life.

Many who come into contact with monks and with Elder Siluan in particular, do not see anything particular in them and thus remain unsatisfied and possibly even disappointed. This occurs because they approach monastics with the wrong scales, with improper demands and expectations.

The monk is engaged in endless struggle, and often very pitched struggle, but an Orthodox monk is not a fakir. He is not interested in the acquisition, through special exercises, of specific psychic powers, which is what so many ignorant seekers of mystical life expect. Monks engage in difficult, constant battle, and some of them, like Elder Siluan, engage in a titanic struggle, invisible to the outside world, to destroy within themselves the proud beast and to become men, real men in the image of the perfect Man — Jesus Christ — humble and meek.

This is a strange life, incomprehensible to the secular world; everything in it is paradox, everything is in a form opposite to the order of the secular world, and it is impossible to explain it in words. The only way to understand it is to perform the will of God, that is, to follow the commandments of Christ; the path, indicated by Him.

Childhood and Early Life

From the long life of the Elder we would like to highlight certain facts which are indicative of his spiritual life and his “history.” The first comes from his early childhood, when he was no more than four years old. His father, like many Russian peasants, would take in pilgrims and travelers. Once, on some holy day, he invited to his home a man carrying books, hoping to hear from this “learned type” something new and interesting, for he was unhappy in his “darkness” and eagerly sought enlightenment and knowledge. At home, the guest was treated to tea and food. Little Semyon with childish curiosity studied the guest and listened closely to his words. The bookworm tried to convince Semyon’s father that Christ is not God and that there is no God. Little Semyon was particularly affected by the words: “Where is He, where is God?” and he thought to himself, “When I grow up, I will travel the world to find God.” When the guest had left, Semyon said to his father: “You teach me to pray, but he said there is no God.” His father answered, “I thought he was an intelligent person, but he turned out to be a fool. Don’t listen to him.” But his father’s answer did not calm Semyon’s apprehension.

Many years passed. Semyon grew up, became a healthy young man and went to work on the neighboring estate of Prince Troubetskoy. He worked as a carpenter with a gang of other workmen. The gang had a cook, an old peasant woman. Once, on a pilgrimage, she visited the grave of the hermit Ioann Sezenovsky (1791-1839) a famed monk. Upon her return, she told of her pilgrimage and of the miracles that happen at the grave. Some of the workers also mentioned the miracles and all agreed that Ioann was a holy man.

Listening to this conversation, Semyon thought, “If he is a holy man, then God must be among all of us, and there is no need to wander the earth searching for Him.” With this thought, his young heart was lifted with love for God.

Somehow, from the age of four to the age of nineteen, the thought that had entered Semyon’s soul during the bookworm’s conversation with his father, a thought that had stayed with him, unresolved, was finally answered in this strange, apparently naive manner.

After Semyon felt that he had acquired faith, his mind was concentrated on the memory of God, and he prayed often with tears. At the same time, he felt an internal change and a desire to become a monk, and, as he later recounted, he began to look on the beautiful daughters of Prince Troubetskoy with love, but not desire, as sisters, though earlier he had been partial to them. At that time he also asked his father to release him to go to the Kiev Pecherskaya Lavra (Monastery), but his father told him categorically, “First you must finish your military service, and then you will be free to go.”

Semyon spent three months in this state, but then it dissipated and he once again resumed his friendship with his peers, took up drinking vodka, chasing after girls, playing the accordion, and in general living like all the other peasant boys his age.

Young, handsome, strong, and by that time wealthy, Semyon enjoyed life. The villagers liked him for his happy and peaceful character, and the girls looked at him as a good marriage possibility. He also fell in love with one of them, and before the question of marriage was resolved, one late night, “something happened.”

Strangely, the next morning, while working with his father, the latter asked Semyon, “Son, where were you last night, my heart was aching.” These meek words fell deep into Semyon’s soul, and later, remembering his father, he said: “I didn’t follow in his footsteps. He was completely illiterate, he even said ‘Our Father’ with mistakes, having learned it by ear in church. But he was a humble and wise man.”

Semyon’s was a large family: father, mother, five sons-brothers and two daughters. They lived together and were content. The older brothers worked with their father. Once, during the harvest, Semyon prepared dinner in the field. It was Friday, but Semyon had forgotten, and so he prepared pork, and everyone ate it. Half a year passed from that day, and one winter holiday, Semyon’s father turned to him with a kind smile: “Son, remember when you fed me with pork in the field? It was a Friday, and you know, I ate it then as if it were carrion.”

— “Why didn’t you tell me then?”

— “I didn’t want to embarrass you.”

In telling about these events from his life in his father’s house, the Elder would add, “This is the type of Elder one should be: he never became angry, always had an even and meek disposition. Think about it: he waited a half-year for a good moment to tell me without shaming me.”

Elder Siluan had great physical strength. Once when he was still young, prior to military service, after Easter he stayed at home when his brothers went out to see friends. Even though he had just had a large meal with meat, his mother made him an entire pot-full of scrambled eggs, at least fifty, and he ate it all.

In those days he worked with his brothers on the estate of Prince Troubetskoy, and on holidays he would sometimes visit the local inn. There were instances when he could drink and entire “quarter” (2.5 liters) of vodka, but still not be drunk.

Once, during a severe frost that followed a thaw, he was staying at an inn. One of the guests who had spent the night there was preparing to return home. He went out to prepare his horse, but soon returned, saying, “Trouble! I must get home, but I can’t: ice has gathered on my horse’s hooves and she won’t let me break it off because it is too painful.” Semyon said, “Come, I will help you.” In the stable he took the horse’s head under his arm and said to the peasant, “Break the ice off.” The horse stood motionless during the entire process, and the peasant was able to ride off.

Semyon could take an entire cast-iron pot of boiling soup from the stove to the table where the gang of workers would be sitting. He could break a thick board in pieces with his fist. He could lift heavy objects and was able to withstand extreme temperatures and great physical labor with little food.

But this strength, which later helped him in his extraordinary struggles, was also the reason for his greatest sin, for which he had to do an extraordinary penance.

Once, during the yearly village religious holiday, Semyon was out walking and singing with friends as all the villagers gathered outside their huts. Two brothers — the village bootmakers — walked toward Semyon and his group. One of these brothers was also very strong, and a troublemaker. This day he happened also to be drunk. He came up to Semyon and tried to take away his accordion, but Semyon managed to pass it to his friend. Semyon began to ask the bootmaker to go in peace, but the latter, wishing apparently to show his strength in front of the entire village, jumped on Semyon. This is how the Elder described the situation:

First I thought it better to retreat, but suddenly I became ashamed by the fact that the village girls would laugh at me, so I punched him in the chest. He flew backward and hit the ground in the middle of the road: blood and froth came from his mouth. Everyone grew frightened and so did I: I thought I killed him. I stood there even as the younger brother of the bootmaker took a big rock and threw it at me. I managed to turn in time, but the rock hit me in the back and I said to him, ‘ Do you want the same treatment?’ I moved on him, but he ran away. The bootmaker lay long on the roadway, but people came to help him, washed him with cold water. It was a half-hour before he could get up, and with great difficulty they brought him home. For two months he was ill, but he lived. I had to be careful from then on because his brothers and friends would lie in wait for me in the evenings with knives and sticks, but God preserved me.

So it was that in the noise of young life the first sound of God’s call to monasticism was drowned out in Semyon’s soul. But God, who had chosen him, soon repeated the call with a type of vision.

Once, after spending some time indulging in earthly pleasures, Semyon fell asleep and in a dream saw that a snake had slid through his mouth inside him. He felt disgusted and awoke. At the same time he heard these words, “You swallowed a snake in your sleep and you are disgusted. That is how unpleasant it is for me to see your actions.”

There was no one in the room. He heard only a voice that spoke those words, a voice that was extraordinary in its kindness and beauty. But the impression that voice made, in spite of its quietness and sweetness, was revelatory. The Elder was deeply and undoubtedly convinced that this was the voice of the Mother of God. To the end of his days he thanked the Mother of God for not forsaking him, for visiting him and helping him rise up from his fall. He said, “Now I see how the Lord and the Mother of God feel sorry for people. Think of it — the Mother of God came down from Heaven to show me, a lad, of the error of my ways.”

He attributed the fact that he was unable to see the Virgin Mary to the unclean state he was in at the time.

This second call, which came not long before his military service, had a decisive influence on his choice of life. The first result of this call was a complete reversal in his lifestyle, which had taken on an unwholesome form. Semyon felt a deep shame for his past and began to ask genuinely for forgiveness from God. The decision to enter a monastery after military service returned with new strength. He acquired a strong sense of sin, and because of this he began to view everything in life differently from before. This different attitude became apparent not only in his own life and actions, but also in his conversations with others.

Military Service.

Semyon’s military service took place in St. Petersburg, in the Life-Guards Sapper Battalion. Leaving for service with a living faith and deep feeling of penitence, he never ceased to remember God.

In the army he was liked as a well-disciplined, calm and orderly soldier. To his comrades he was a loyal and trusted friend. This was in fact, typical of the Russian army as a whole, where soldiers lived together as brothers.

Once, during a holiday, he went with three soldiers from his battalion to a large tavern in the capital, where there was much gaiety and music. A dinner with vodka was ordered and the group began to talk loudly. Semyon remained mostly silent, and one of his friends asked,

“Semyon, you are so quiet, what are you thinking about?”

“I am thinking: here we are in this tavern, eating, drinking vodka, listening to music and having a good time, and meanwhile on Mt. Athos monks are keeping the vigil and will pray all night. So, who of us will give a better answer on Judgment Day — we or they?”

Then another said,” What a strange character you are, Semyon! We are listening to music and having a good time, and your mind is on Mt. Athos and Judgment Day!”

The words of this Guards soldier, that Semyon’s “mind is on Mt. Athos and the Judgment Day,” are applicable not merely to the moment when they were all sitting in the tavern, but to the entire period of his military service. His thoughts of Athos were also apparent in the fact that he sent money there on several occasions. One day he was walking from the Ust-Izhora camp, where the battalion was quartered in the summer, to the Kolpino post office to send a donation to Mt. Athos. Upon his return, not far from Kolpino, a rabid dog ran toward him. As it approached and prepared to bite him, he could only exclaim in fear, “Lord, have mercy!” As soon as the words left his mouth, some force pushed the dog aside as if it had encountered a wall; circling Semyon, it ran off toward a nearby village, where it bit a number of people and cattle.

This event left a deep impression on Semyon. He personally felt the proximity of God, who had saved him, and his faith became even stronger.

Having finished his military service, before departing for home, Semyon and the company clerk went to visit Father Ioann of Kronstadt to ask for his prayers and blessing. However, Father Ioann was absent from Kronstadt, so they decided to leave him letters instead. The clerk began to write a long letter in his best handwriting, but Semyon wrote only a few words: “Father, I wish to become a monk. Pray that the world does not detain me.”

They returned to their barracks in St. Petersburg and, in the words of the Elder, the very next day he felt that all round him “the flames of hell were burning.”

Leaving St. Petersburg, Semyon returned home, but he spent only one week there. Clothes and presents were collected for him to take to the monastery. He said good-bye to everyone and departed for Mt. Athos. But from the day that Father Ioann of Kronstadt prayed for him, “the flames of hell” burnt round him no matter where he was: on the train, in Odessa, on the ship and even in the monastery on Mt. Athos, in church, everywhere.

Arrival on the Holy Mountain. Deeds as a monk.

Semyon arrived on the Holy Mountain in the autumn of 1892, entering the Russian monastery of the holy martyr St. Panteleimon. Thus began his new life as a monk.

According to the customs of Mt. Athos, the novice “brother Simeon” was to spend a few days in complete calm, so as to ruminate on the sins of his life, and, having written them down, confess them to his priest. The hellish suffering he had endured brought forth in him a complete and sincere repentance. During the sacrament of Confession, he sought to free his soul from all that weighed on it, and for this reason he willingly and fearfully, without a trace of self-righteousness, confessed all the sins of his life.

His confessor then said to him, “You have confessed your sins before God, and know that they are forgiven… Now you must prepare to lead a new life… Go in peace and be joyous that the Lord has led you to this harbor of salvation.”

Brother Simeon was prepared for spiritual feats by the centuries-old tradition of monastic life on Mt. Athos, filled with the ever-present memory of God: prayer in the cells alone, lengthy common services in the church, fasts and vigils, frequent confession and communion, reading, work, and works of penance. Soon he learned the Prayer of Jesus on the rosary. Only a brief while later, some three weeks, one evening during prayer before an icon of the Mother of God, the prayer entered his heart and continued to repeat there day and night, but it was some time before Simeon appreciated the greatness and rarity of this gift, received from the Mother of God.

Brother Simeon was patient, mild, and obedient; in the monastery he was held in high regard as a good worker of fine temperament, and this pleased him greatly. It was then that thoughts began to creep into his soul, such as, “You live a saintly life, you have repented, your sins have been forgiven, you pray incessantly, and you fulfil your obligations well.”

These thoughts disturbed the mind of the novice and worried his heart, but due to his inexperience, Simeon did not know what to make of these feelings.

One night, his cell filled up with a strange light, which showed through even his body, so that he could see his organs inside. A thought came to him, “Take this — it is grace,” but his soul was confused, and he was left in a state of great anxiety. After seeing the strange light, he was visited by demons, and out of naivete he spoke with them, “as with people.” Their visits became more frequent; sometimes they would say, “You are now a saint,” and sometimes, “You will not be saved.” Brother Simeon once asked a demon, “Why do you say such contradictory things: on the one hand I am holy, and on the other I will not be saved?” The demon laughed in answer, “We never tell the truth.”

Contrary demonic insinuations, lifting him to heights of pride and throwing him into the depths of eternal damnation, burdened the soul of the young novice, bringing him to the verge of despair and causing him to pray with increasing fervor. He slept little and in brief spells. Physically strong, of heroic stature, he did not lie down in bed, but spent his nights in prayer either standing or sitting on a stool. When exhaustion overcame him, he would sleep for 15-20 minutes on his stool, and then rise again for further prayer.

Months passed, but the suffering of demonic visits only intensified. The young novice’s spiritual strength began to falter, his courage was exhausted, the fear of death and despair gripped him, and a horrible feeling of hopelesness took hold of his entire being more and more often. Finally, he reached the brink of his despair, and, sitting in his cell one evening, concluded that, “It is impossible to reach God through prayer.” With this thought he felt completely forlorn, and his soul darkened with hellish languor and anguish.

The same day, during vespers, on an icon of the Savior outside the church of the Holy Prophet Elijah by the windmill, he saw the Living Christ.

“The Lord mysteriously revealed himself to the young novice,” and his entire body, his entire being, was filled with the fire of grace of the Holy Spirit, the same fire that the Lord brought to earth during His Coming (Luke 12:49). From this vision, Simeon fainted, and the Lord disappeared.

It is impossible to describe Simeon’s condition in this hour. He had been sanctified by the glorious light of God, as though he had been removed from this world and spiritually transported to the heavens, where he heard unspoken words. At this moment, he was as though born anew from on high (John 1:13; 3:3). The meek gaze of the all-forgiving, all-loving, joyous Christ drew to Him his entire person, and having disappeared, continued to vitalize his soul with the sweetness of God’s love through the vision of God outside the confines of worldly objects. Later, in his writings, Simeon often repeated that he came to understand the Lord through the Holy Spirit, that he saw God in the Holy Spirit. He also insisted that when the Lord Himself visits a soul, the soul cannot but recognize him as its Creator and God.

Comprehending its resurrection and having seen the light of true and eternal being, Simeon’s soul experienced the joy of the Pascha for some time following this vision. Everything was great: the world was wonderful, people were nice, nature indescribably beautiful; and his body seemed different too: it was lighter and he appeared to have greater strength. But slowly the feeling of grace began to weaken. Why? What could be done to avoid its loss?

The search for an answer to this puzzle was sought in the advice if Simeon’s spiritual guide and the writings of the ascetic Holy Fathers. “During prayer keep your mind free of all imagination and thought and concentrate it in the words of the prayer,” admonished the Elder Father Anatoly of Holy Rusik. Simeon talked much with Elder Anatoly, who concluded his useful and didactic teaching with the words, “If you are already such, where will you be in old age?” Without wishing it, Anatoly’s astonishment gave the young novice a strong push toward vanity, which Simeon did not yet know how to vanquish.

The young and inexperienced Simeon now embarked on the most difficult and complicated struggle against vanity. Pride and vanity bring with them all manner of sorrows and falls: grace disappears, the heart grows colder, prayer becomes weaker, the mind is distracted and various passions take root.

Now a monk, Siluan gradually becomes more adept at ascetic works, most of which appear impossible to the common man. His sleep remains fitful: 15-20 minutes several times a day. As before, he does not lie down, but sleeps sitting on his stool; in the daytime he labors as a worker; he follows the precepts of internal obedience and learns to submit his own will in order to more fully commit himself to doing the will of God; he abstains from food, talk, and extraneous movement; spends lengthy periods praying the Prayer of Jesus. And despite all this spiritual exertion the feeling of grace often leaves him, and at night he is surrounded by demons.

The constant change of condition from a feeling of some grace to a feeling of hopelesness in the face of demonic attack does not pass without bringing fruit. In this state of perpetual change, Siluan’s soul becomes accustomed to constant internal battle, vigilance, and the diligent search for a solution.

Fifteen years passed since his vision of Christ. And one day, during a struggle with the demons, when, despite his efforts, it proved impossible to achieve a clear state of mind for prayer, Siluan rose from his stool to prostrate himself, but saw before him an enormous demon, obscuring the icon and expecting to take Siluan’s bow for himself. The entire cell was full of demons. Father Siluan sat down again on his stool, and, head hung low, with heavy heart prayed, “Lord, you see that I wish to pray to you with a clear mind, but the demons won’t let me. Teach me what I must do so that they cannot distract me.” And the answer came from within his soul, “The proud always suffer like this from demons.” “Lord,” said Siluan, “teach me what I must do to humble my soul.” Once again the answer came from his heart: “Keep your mind in hell and don’t lose hope.”

From this moment he saw not in an abstract or intellectual manner, but with his entire being that the root of all sin, the seed of death is pride; that God is Meekness, and the person seeking to win God must win meekness. He understood that the indescribable sweetness of Christ’s meekness that he had been given to experience during the Vision, was an inseparable aspect of God’s love, God’s being. From this moment he truly understood, that his entire spiritual labor must be directed toward attaining meekness. Thus with his own being, he was able to comprehend this great mystery of Being.

In this manner, his soul was exposed to the mystery of the struggle of Serafim of Sarov, who, following his vision of Christ in church during the Liturgy, also experienced a feeling of having lost grace and contact with God; who stood for a thousand days and nights in a desert on a rock, calling, “God, have mercy upon me, a sinner.”

He finally saw the true meaning and force of Saint Pimen the Great’s answer to his disciples, “Believe, my children! Where Satan is, there I will be.” He understood that Saint Anthony the Great was sent by God to a shoemaker in Alexandria to learn the same lesson: from the shoemaker he learned to think, “All will be saved, only I will perish.”

He understood from the experience of his life that the field of spiritual struggle with evil, cosmic evil, lies within a person’s own heart. He saw with his soul that the tap root of sin is pride, that curse of mankind that tore people from God and thrust the world into endless sorrow and suffering; pride was that true seed of death that had enveloped mankind in the darkness of despair. From this moment, Siluan, now a spiritual giant, turned all his energies toward acquiring the meekness of Christ, which he was given to witness during his first Vision, but which he had not then been able to keep.

Now the monk Siluan stood firmly on the path of righteousness. From this day, his “favorite song,” as he called it, became, “Soon I will die, and my cursed soul will descend into the closed black confines of hell, and there I alone will burn in a dark flame and cry for the Lord, ‘Where are You, light of my soul? Why have You deserted me? I cannot live without you’.” This prayer led to peace in Siluan’s soul and to clarity in prayer, but even this flaming path was not a short one.

Grace does not desert him as before. He feels it in his heart, he feels the living presence of God, God’s mercy fills him with wonder, he experiences the depth of the world of Christ; the Holy Spirit once again fills him with the power of love. And though he is no longer as foolish as before, and though he has emerged wiser from the long and arduous struggle, though he is now a great spiritual wrestler, yet still he suffered from the inconstancy and mutability of human nature, and his heart cried with an inexpressable sorrow when he felt grace slipping from him. And this continued for fifteen more years, until one day he acquired through one sweeping exercise of the mind, invisible on the outside, the ability to vanquish that which had for so long defeated him.

By way of clear internal prayer, the ascetic learns the great mysteries of the soul. Entering his heart with his mind, first he finds his human heart, within which he sees, deeply hidden, the heart whose essence is not human at all. He finds this deeper heart, this spiritual, metaphysical heart, and discovers that the being of humanity is not something alien or external to him, but is organically connected to his own personal being.

“Our brother is our life,” taught the Elder. Through Christ’s love all people are accepted as an indivisible part of our own personal eternal being. The commandment to love your neighbor as you would yourself, he begins to understand as something other than a mere ethical norm; in the word “as” he sees not an indication of the level, or measure, of love, but a sign of the ontological commonality of being.

“The Father does not judge, but has given judgment to the Son… because He is the Son of man” (John 5:22-27). This Son of man, the Great Judge of the world, on Judgement Day will proclaim that “the one among the smallest of these” is Himself; in other words that the being of each individual is held in common with Him, and is included in His own personal being. All of humanity, “all of Adam,” he has taken into himself and has suffered for all of Adam.

After the experience of the torments of hell, after God’s admonition to “Keep his mind in hell,” it became a habit of Elder Siluan to pray for the dead suffering in hell. But he prayed also for the living and for future generations. His prayer, which was not bound by temporal limits, erased any trace of the transient features of human life, and of enemies. He was given in the sorrow of the world to distinguish between those who experienced God and those who did not. It became unbearable for him to consider that people could languish in the depths of darkness.

Once a hermit-monk said to him that “God would punish all atheists. They will burn in an eternal flame.” It appeared to give this monk satisfaction that they would be punished by eternal fire. But Elder Siluan, with some worry, asked, “Tell me please, if you are placed in Heaven, and from there you see how others burn in hellish flames, would you remain detached?” “What can you do — it’s their own fault,” countered the monk. The Elder, filled with sorrow, answered, “Love cannot accept that… Everyone must be prayed for.”

And indeed, he prayed for everyone; to pray only for himself became a foreign concept. All people are disposed to sin, and all are stripped of God’s glory (Romans 3:22). For Siluan, having been exposed to the glory of God and having been denied it, the very thought of such denial was too heavy to bear. His soul languished in the consciousness that people live without knowing God and His love, and he prayed with great prayer that the Lord through his inscrutable love should allow them to know Him.

Till the end of his life, despite waning strength and sickness, Siluan continued to sleep for only brief spells. He had much time for individual prayer, and he remained in prayer constantly, changing its form to fit circumstances. He prayed especially strongly at night, before the matins. That was when he prayed for the living and the dead, for friends and enemies, for the entire world.