During the First World War, while politicians prevaricated, Romania’s British queen lobbied for entry on the side of the Allies and courted the international press, becoming the glamorous face of her adopted country’s war effort.

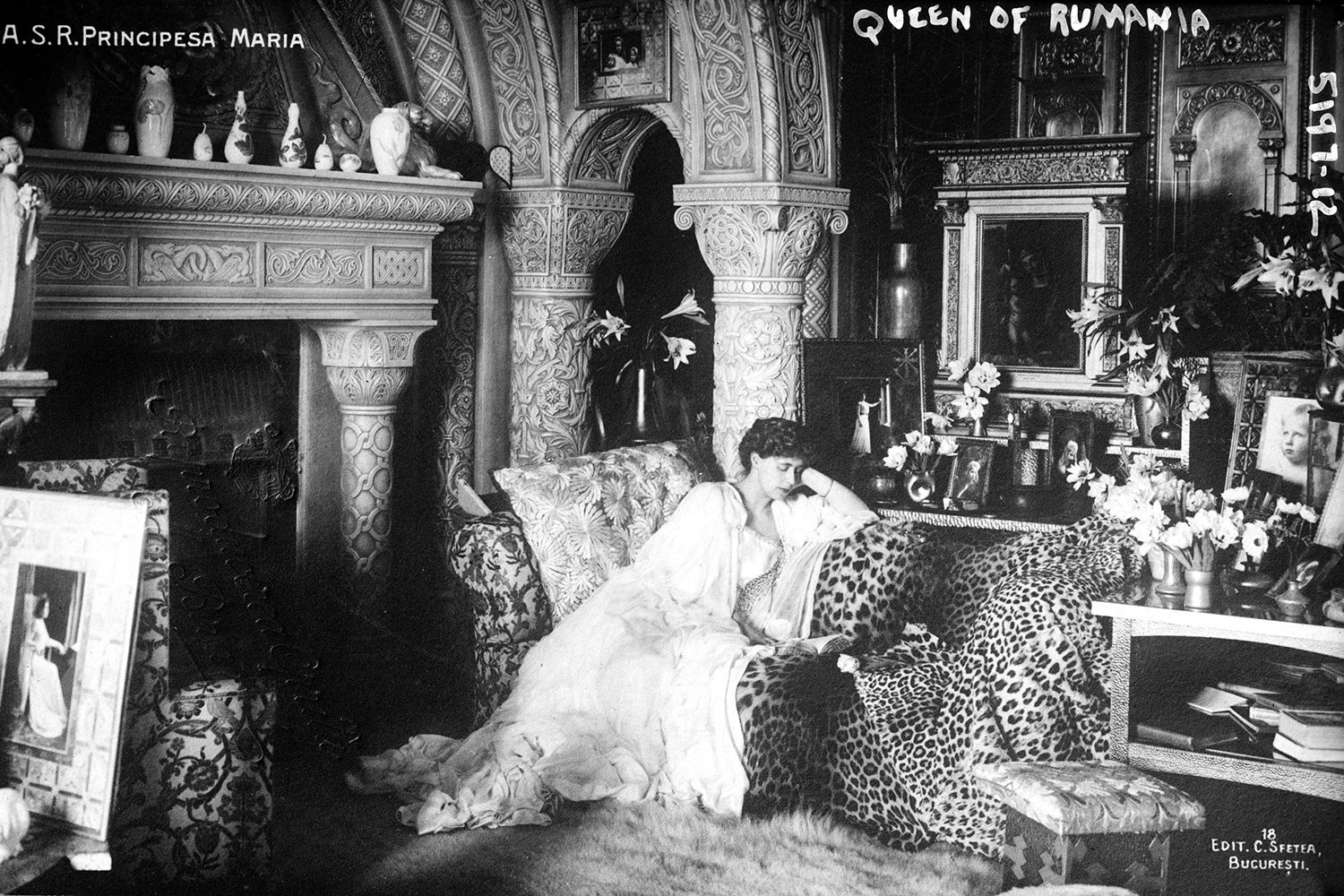

Queen Marie of Romania, 20th century.

Queen Marie of Romania, 20th century.

Returning from a whirlwind visit to France and England during the first months of the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Queen Marie of Romania proudly proclaimed she had successfully given her country a ‘face’. Romania’s uncompromising prime minister Ion Brătianu – derided as desperate, ‘beetle-browed’ and byzantine by Western politicians – had the nous to realise that, in their eyes, his English-born, thoroughbred monarch was the perfect antidote to his perfidious Balkan traits, hence Marie’s invitation to Paris. In the summer of 1918 Marie had been described by the New York Times as ‘one of the vivid and unforgettable personalities of the war’.

That Romania’s queen should hog the limelight at the biggest political gathering the world had ever seen was not something anyone would have predicted in 1914. While Serbia had little option but to plunge into war that August, Romania, along with Bulgaria and Greece, initially remained neutral. Two Balkan conflicts in the two preceding years had left those countries wary of premature commitment to the wrong side and with competing land claims that precluded a Balkan alliance. The bloody deadlock that defined so much of the conflict made neither the prospect of entry enticing nor the ultimate victor predictable. By the end of 1915, Bulgaria had sided with the Central Powers and Serbia had been routed. Romania continued to prevaricate.

Crown prince Carol II, King Ferdinand I and Queen Marie of Romania, 1922.

Crown prince Carol II, King Ferdinand I and Queen Marie of Romania, 1922.

When war broke out, the Danubian state was a relatively new country, having emerged from Ottoman and Russian suzerainty in the latter half of the 19th century. The two principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia united in 1859, although in an era when the hallmarks of Great Power support and imported European royalty conferred both stability and legitimacy, it wasn’t until 1881 – in the wake of the Russo-Turkish war of 1878 – that the Romanian Kingdom was officially born. Carol I, a member of the Hohenzollern Dynasty, became the country’s first monarch and throughout his long reign he remained loyal to his roots, committing Romania to a secret alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary.

The events of 1914 put him at odds with his government. Carol wanted to honour his commitment to the Triple Alliance, while many among Romania’s elite saw the war as an opportunity to fulfil the nation’s irredentist ambitions of acquiring Transylvania – long considered the cradle of their nation – from the Habsburg Empire. Perhaps the decision to remain neutral contributed to Carol’s death in October that year; by then an old man, he was wracked with the failure to fulfil his word. The king’s passing saw his unremarkable nephew Ferdinand (also a Hohenzollern, German-born and Prussian-trained) accede to the throne. Here was an unprepossessing man who the prime minister, Ion Brătianu, could easily dominate. Even better, Ferdinand was accompanied by a considerable asset – his ambitious, popular, handsome wife, Marie, who boasted good relations with first cousins ‘Nicky’, Tsar of Russia, and Britain’s George V.

Rumour has it that George once had romantic inclinations towards the young princess; certainly as members of an expansive club – British-born royalty who claimed Queen Victoria as their grandmother – the pair had fond memories of each other from childhood and their letters were peppered with affectionate terms. The same was true of Marie’s missives to Nicholas II. Her mother was Grand Duchess Marie Alexandrovna, daughter of Tsar Alexander II. This link to the Orthodox East partially explains why Marie, the prettiest of the Duke of Edinburgh’s children, was married off at just 17 in 1893 to a plain German prince in a country Victoria considered both ‘insecure’ and ‘immoral’.

Panorama of Bucharest, probably from a German zeppelin, 1916.

Panorama of Bucharest, probably from a German zeppelin, 1916.

Initially the entitled English princess found her apprenticeship in an Eastern European backwater a challenge. Beyond the occasional mention in society magazines she rarely featured on the international stage. By 1914, however, Marie had grown fond of her adopted country and was well placed to assume a formal role in determining Romania’s wartime direction. Her lover, Prince Barbu Ştirbey, an adroit backroom courtier and the prime minister’s brother-in-law, provided Marie with intimate access to the country’s political scene, while her weak husband left the queen plenty of room to manoeuvre in favour of the Entente.

Stuck with the purgatory of indecision for two years during which double-dealings, foreign suitors and black market money became the hallmarks of Romania’s wartime hesitation, Marie admitted she hated neutrality, likening it to walking on eggshells. She underestimated her rising stock both in Romania and among diplomats desperate to woo the bell-weather state into battle. Ambassadors on both sides quickly recognised Marie’s leverage at court, while her direct appeals to both Russian and British royalty were utilised by a Romanian government wracked with a small-state fear of being overlooked and misunderstood.

On 27 August 1916 the queen wrote in her diary: ‘I awake this morning knowing what is going to be – I have known for many weeks – one of the only ones who have known it – I know it is going to be war. War!’ Under pressure from France and Britain, Romania had finally committed to the side of the Entente and declared war on Austria-Hungary. Initially Marie was concerned about her own role: ‘What can a woman do in a modern war? It is no more the time of Joan of Arc.’

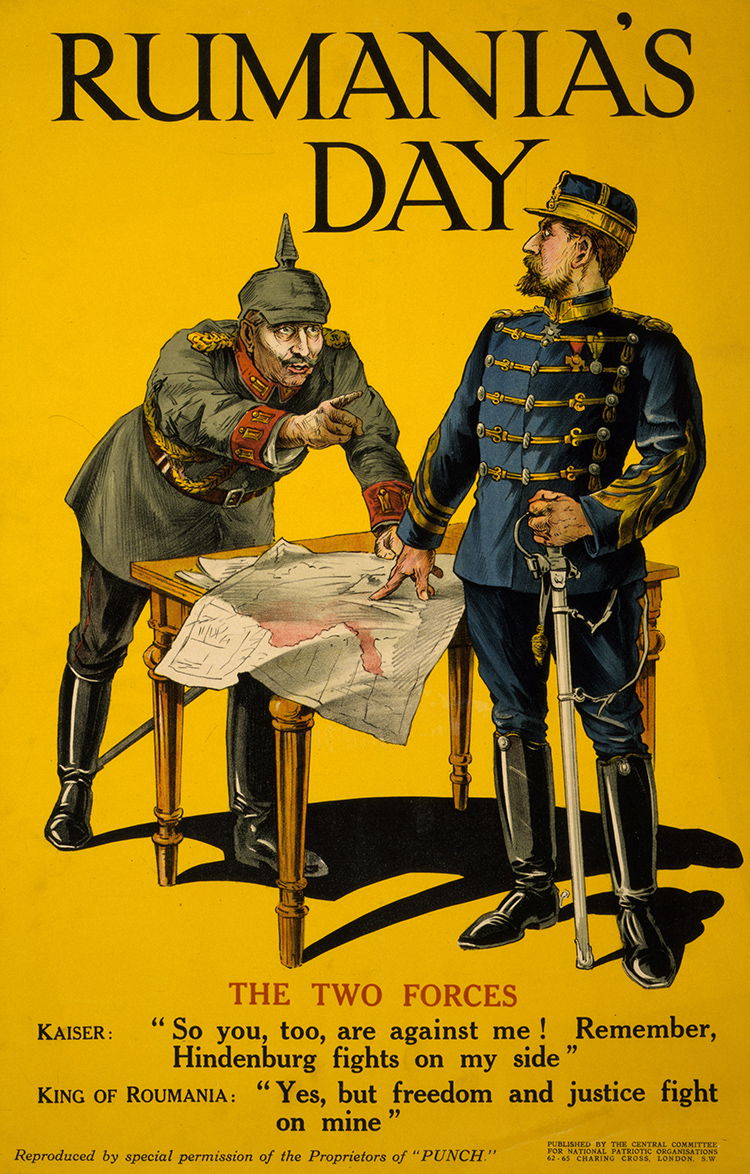

British propaganda poster welcoming Romania’s decision to join the Entente.

British propaganda poster welcoming Romania’s decision to join the Entente.

Despite a brief hiatus, which saw Romania’s fêted ‘peasant-soldiers’ successfully invade Transylvania, the army soon collapsed and with it the conviction of both the prime minister and the king. German Field Marshal August von Mackensen caught Romania in a lethal pincer movement and duly occupied Bucharest in December 1916. It was a terrible result not only for beleaguered Romania but for Entente morale generally. Only three months earlier the British and French press had gleefully described Romania’s entry into the war as the ‘beginning of the end’. Few anticipated the rapid and ignominious retreat that followed. The Spectator predicted that Romania would now disappear off the news agenda; they didn’t anticipate the tour-de-force that would be delivered by Marie.

Marie’s predecessor was Carol’s wife, German-born Queen Elizabeth, better known by the nom-de-plume Carmen Sylva. Renowned for her writing, in particular folkloric stories inspired by the superstitions and beauty of her adopted land, Elizabeth was a promoter of the arts and her writing had given Romania a fairytale sheen that was absent among its Balkan neighbours.

Romania’s entry into the war provided Marie with a fresh opportunity to showcase the little-known country (with herself as its supreme custodian) in front of a Western audience. Her book My Country was published in Britain, France and later the US. It positioned Romania as a spiritual, rustic land and appealed to an Edwardian nostalgia much in demand during the quagmire of war. In late 1916, sections of My Country were serialised in The Times. It was a period of extraordinary personal adversity for the queen. In the space of a couple of months, her youngest son died of typhoid fever, bombs targeted her palace and she was forced to abandon Bucharest and retreat north. But the Entente had found a much needed, sympathetic heroine who was more than willing to play the part.

In the wake of Edith Cavell’s execution in 1915, the stock of the wartime nurse had never been higher. Marie quickly capitalised on this; rarely seen out of pressed whites, the Red Cross on her forehead, she lead an entourage of women around hospital wards and Romania’s stricken soldiers on the front line. Foreign legations were startled by Marie’s work ethic among the injured and dying holed up in Romania’s last unoccupied area of land, where by early 1917, typhus was rampant. The French ambassador marvelled at Marie’s apparent invincibility; she worked all hours and refused to take precautions when tending the infected troops. ‘Don’t you think it gives them more pleasure to kiss my uncovered hand?’ she queried, rejecting the offer of protective gloves.

The queen had an unrivalled ability to cultivate the emerging mass media. Frequently in her diaries she referred to foreign cinematographers and photographers who visited her at work. A British Pathé newsreel shows a sanitised version of plucky Romania holding out against the odds, with Marie the embodiment of her nation in startling white, distributing trinkets, flowers and good will among her desperate compatriots.

America’s entry into the war saw Marie’s story catapulted across the Atlantic. Without their own monarchy and before the cult of the First Lady and Hollywood royalty had taken off, America embraced Marie. She was featured in numerous journals and newspapers; Century Magazine waxed lyrical about ‘The Soldier Queen’ – a solitary woman who ‘has been worth a whole army corps to Rumania.’ For the New York Times she was ‘Rumania’s Heroic Soldier Queen.’ By the spring of 1917 the tsar had abdicated, his unpopular tsarina was gone and yet here was Marie in neighbouring Romania, a national heroine credited for boosting morale and contributing to the extraordinary resurgence of the Romanian army that held off the Germans in the summer of 1917. As Romanian historian Lucian Boia writes, Marie ‘proved that a woman, while remaining feminine, could win a game normally reserved for men.’ Certainly there was no more appealing symbol for the dismal Allied effort in the East.

The First World War was famous for its deleterious impact on royalty. It destroyed four of the leading five monarchies of Europe. Britain’s royal family was the only major survivor and George V was forced to change the family name to Windsor. Marie bucked this trend as Bolshevism rampaged along Romania’s borders. Although abandoned by its ally Russia, Romania was criticised for capitulating to Germany in March 1918. The queen was undeterred, grabbing headlines for defying the kaiser – ‘We must fight to our last man!’ She refused to co-operate with the Germans and insisted Ferdinand did the same.

By December 1918, alongside the king and Romania’s French military saviour, General Henri Berthelot, the queen, in military uniform, rode triumphantly back into Bucharest, claiming her position as the Empress of Greater Romania. Although not ratified internationally, at war’s end Romania looked set to make major territorial gains. Given his queen’s popularity, it is no wonder that Prime Minister Brătianu, known for ‘having entered the war too late and surrendered too soon’, called upon Marie to join him for the pending showdown in Paris between the Great Four and numerous small nations with their competing claims.

Queen Marie, 1910.

Queen Marie, 1910.

Marie accepted the challenge with relish, welcoming the press into her train upon arrival in the French capital, hosting meetings in her Ritz suite, playfully flaunting her femininity with the British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour and clinching meetings with all of the big three – Wilson, Lloyd George and Clemenceau (although Democrat Wilson had little time for a mere ‘Queen’, especially one from a country that had refused to enfranchise its considerable Jewish minority). A stint across the Channel to stay with the other royal survivor, George V, again saw her ruffle a few feathers. George was a man who considered newspapers no more than ‘filthy rags’. But the momentum was with Marie. Press coverage in March 1919 confirms that the queen’s belief in her own popularity wasn’t mere hubris. The Daily Mail picture page frequently chose Marie over the politicians she dismissed as ‘tired, bored statesmen around a green table’.

The queen’s flamboyant style (hats, veils, brocade and furs) was regularly noted as the paper charted her movements from Paris to London, where she and her daughters stayed in the same Buckingham Palace suite that President Wilson had recently vacated. Punch made Marie’s claims for ‘starving’ Romania front-page news and the Mirror framed her as an anti-Bolshevik feminist pin-up. Marie successfully scored political points for her hungry country, compensating for Romania’s sidelined status at the Conference (deeply unpopular Brătianu was incensed he should have one fewer delegate than Belgium and Serbia). Britain’s First Lord of the Admiralty, Walter Long, declared she had ‘been the most astonishing propagandist he had ever seen’. It is telling that after four years of diplomacy and propaganda in a man’s world, it was Marie who sounded a note of caution: ‘One woman’s word cannot change the face of such big events.’ Perhaps not, but Romania, which doubled in size in the aftermath of the war becoming the fifth biggest country in Europe, could not have hoped for a better ambassador.

Tessa Dunlop is the author of To Romania with Love and is completing her doctorate on Romanian Identity during the First World War. She will give a lecture as part of an evening to commemorate Queen Marie’s wartime legacy at the Romanian Cultural Institute, 21 November 2018. www.icr-london.co.uk

Tessa Dunlop | Published 06 November 2018